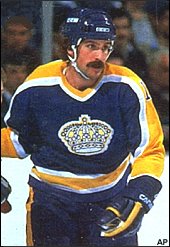

Bob Berry got his first taste in the NHL with the Montreal Canadiens, but will always be best known as a player as a member of the Los Angeles Kings. To another generation he will best be remembered as a long time coach.

A 20 year old Berry spent the 1963-64 season between the QJHL's Verdun Maple Leafs and the OHA's Peterborough Petes. As opposed to taking a shot at the pros, Berry, an intelligent student, opted to attend George Williams College where he also starred on the hockey team for 3 seasons. Upon graduation, he turned to the Quebec Senior League where he starred with the Hull Nationals.

The Montreal Canadiens secured his NHL rights a while back finallly Berry turned pro. He spent his first two seasons playing in the American Hockey League. He did see action in two games with the Habs in the 1968-69 season.

Well Berry will always cherish his two games wearing the CH, his best memories came in a LA Kings jersey. The Habs sold him to Los Angeles in 1970.

Berry went on to play 7 full seasons with the Kings. His most successful seasons came when he was paired with center Juha Widing and right winger Mike Corrigan. The trio, dubbed the Hot Line by LA media, were an essential cog in the Kings attack in the early 1970s. Berry recollected on his days on the Hot Line:

"All three of us provided some balanced scoring and with the other two centers, Bob Nevin and Butch Goring, contributing as well we were a tough opponent almost every night."

Berry was the best known of the three. He twice represented the LA Kings as their selection to play in the All Star game - in 1973 when he scored a career high 36 goals and 64 points, and in 1974 when he scored 56 points. In all, Berry scored 159 goals and 350 points in a purple and gold Kings jersey.

Berry enjoyed his time on the west coast:

"My NHL career was with the Los Angeles Kings and I'll always look back on those days with fondness. During my seven seasons we accomplished a lot of positives and in particular the 1974-75 season stands out. That season we had a great bunch of guys...a lot of guys from other organizations...Rogie Vachon, Terry Harper, Bob Murdoch, Dan Maloney, Bob Nevin and Mike Murphy. These were character players and with the coaching of Bob Pulford we put together a 105 point season (still a club record)."

One guy Berry had much respect for was Pulford.

"Playing for Bob Pulford was a great experience. He taught everyone the value of hard work and team work. We had nine players that season who played in every game, we were well balanced and all three lines were dangerous with the puck and had responsibilities from a defensive standpoint."

Following his playing days Berry turned to coaching. Berry has been a fixture behind the bench for many years, either as a head coach or an assistant.

Glenn Goldup

This is Glenn Goldup, the son of former NHL forward Hank Goldup.

Born in St. Catharines, Ont., he grew up in suburbs of Toronto. In fact, he grew up playing his youth hockey in the same Humber Valley minor hockey program that produced future NHL teammate Ken Dryden.

Glenn went on to play his junior hockey starring for the Toronto Marlboros and had 42 goals and 53 assists in 54 games in his final season.

"We won the Memorial Cup that year and that was the highlight of my career," he recalled "I think we lost only six or eight games all season. In the past the Marlies always had one strong line and played it to death, but George Armstrong was our coach, and he used all three lines on the power plays and to kill penalties, and it didn't matter if we were down three or four goals going into the final period, we were always confident that we could pull it out."

Goldup played on a line with Wayne Dillon and Mark Howe, which surpassed all the team scoring records previously set by the line of Steve Shutt, Billy Harris and Dave Gardner.

Goldup was a second-round draft pick of the Canadiens in 1973 and spent parts of three seasons with the team while also playing in the minors at Nova Scotia and Fort Worth. He helped Nova Scotia win the Calder Cup as AHL champions in 1976 - one of his proudest moments in his hockey career.

He played 291 games in the 1970s, mostly with the Los Angeles Kings even though he was originally a Montreal Canadiens prospect. Those 70s Montreal teams were very deep and Goldup could not get into the line up regularly. So the Habs traded Goldup and 1978 third-round pick (later traded) to Los Angeles for 1977 third-round pick (Moe Robinson) and 1978 first-round pick (Danny Geoffrion) in 1976.

"Playing in Los Angeles was a distraction at first," he said. "But once I got over all the hype I found it was a great situation because I didn't have to wear an overcoat and I didn't have to start my car 10 minutes early because of the cold."

Goldup retired from pro hockey in 1983. In 291 NHL games he scored 52 goals and 67 assists for 119 points. He retired and moved back to Toronto. He sold cars initially but later found success as an account executive for sports radio station Fan 590.

Born in St. Catharines, Ont., he grew up in suburbs of Toronto. In fact, he grew up playing his youth hockey in the same Humber Valley minor hockey program that produced future NHL teammate Ken Dryden.

Glenn went on to play his junior hockey starring for the Toronto Marlboros and had 42 goals and 53 assists in 54 games in his final season.

"We won the Memorial Cup that year and that was the highlight of my career," he recalled "I think we lost only six or eight games all season. In the past the Marlies always had one strong line and played it to death, but George Armstrong was our coach, and he used all three lines on the power plays and to kill penalties, and it didn't matter if we were down three or four goals going into the final period, we were always confident that we could pull it out."

Goldup played on a line with Wayne Dillon and Mark Howe, which surpassed all the team scoring records previously set by the line of Steve Shutt, Billy Harris and Dave Gardner.

Goldup was a second-round draft pick of the Canadiens in 1973 and spent parts of three seasons with the team while also playing in the minors at Nova Scotia and Fort Worth. He helped Nova Scotia win the Calder Cup as AHL champions in 1976 - one of his proudest moments in his hockey career.

He played 291 games in the 1970s, mostly with the Los Angeles Kings even though he was originally a Montreal Canadiens prospect. Those 70s Montreal teams were very deep and Goldup could not get into the line up regularly. So the Habs traded Goldup and 1978 third-round pick (later traded) to Los Angeles for 1977 third-round pick (Moe Robinson) and 1978 first-round pick (Danny Geoffrion) in 1976.

"Playing in Los Angeles was a distraction at first," he said. "But once I got over all the hype I found it was a great situation because I didn't have to wear an overcoat and I didn't have to start my car 10 minutes early because of the cold."

Goldup retired from pro hockey in 1983. In 291 NHL games he scored 52 goals and 67 assists for 119 points. He retired and moved back to Toronto. He sold cars initially but later found success as an account executive for sports radio station Fan 590.

Charlie Simmer

It took him a few seasons, but by 1979-80 Charlie Simmer had established himself as one of the most prolific scorers of his time.

It took him a few seasons, but by 1979-80 Charlie Simmer had established himself as one of the most prolific scorers of his time.Then tragedy struck.

Despite scoring 45 goals and 99 points in his only season of major junior hockey with the Soo Greyhounds, "Chaz" wasn't drafted until 39th overall in 1974. The California Golden Seals selected him in the 4th round.

Simmer never got untracked in California or Cleveland (the Seals moved to Ohio in 1976). He was released and signed as a free agent with the Los Angeles Kings, the team where he would become famous.

It wasn't an instant hit though. Simmer spent a year and a half in the minors. In fact he almost quit hockey altogether before finally catching on with the Kings full time in 1978-79. He finished the year with a very impressive 21 goals and 48 points in 38 games.

Moved to the left wing, Simmer was a perfect match on a line with Marcel Dionne and Dave Taylor. The trio were quickly dubbed the Triple Crown line - one of the most famous units in hockey history.

For those who didn't notice Simmer's late season exploits, Simmer continued his excellence in the following season, leading the league in goal scoring with 56 goals. He added 45 assists for 101 points in just 64 games. He set the modern day NHL record with goals in 13 consecutive games.

In 1980-81, Simmer and New York Islanders superstar Mike Bossy both chased down Maurice "Rocket" Richard's legendary mark of 50 goals in 50 games. Bossy equaled the record, but Simmer fell just short. Simmer scored a hat trick in the 50th game of the year, but fell one shy with 49 goals in 50 games. He ended up with just 7 more goals, as he was limited to just 65 games.

A terrible injury ended Simmer's dream season on March 2, 1981. During a game in Toronto, Simmer's right leg was shattered. He didn't skate again until late November. His damaged leg was held together by a metal plate and nine screws.

Simmer's 1981-82 season was a tough one. He spent most of the year learning to play with his bad leg. He got into 50 games, scoring 15 times. Much of his ice time was limited to spot duty and power play shifts. By the playoffs he was regaining his old form, scoring 4 goals and 11 points in 10 games.

"I had to start out early with spot duty and power play shifts. And the biggest thing was to develop confidence that I could depend on the leg. You've got to be able to play without even thinking about it."

Simmer did learn to trust his leg, and also regained his speed. He wasn't a speedy player by any means, but for a man of his size, he had a surprising, powerful burst in his stride.

Simmer returned to a point a game form in 1982-83, scoring 80 points in a full 80 games. However only 29 of those points were goals. While he played his first full healthy season, the goal scoring machine seemed to be missing some of its potent cogs.

Simmer was able to return to his goal scoring form in 1983-84. He scored 44 times in 79 games, while adding 48 assists for 92 points. Most of his goals, as always, were garbage goals. He had a powerful wrist shot and fired the puck from anywhere, but like Tim Kerr he learned he was immovable in front of the net and a scoring machine in the slot.

Following an ugly contract dispute, the Kings traded Charlie to Boston after just 5 games in 1984-85. In Boston Charlie put together some nice seasons. He scored 34 goals his first year. In 1985-86 he was having one of his best seasons ever, but as usual he saw it ended by injury. Simmer got into only 55 games, but scored 36 goals.

Simmer appeared in all 80 games in '86-87, scoring 29 goals and 69 points. He spent one more year in the NHL, with the Pittsburgh Penguins. He bowed out quietly, scoring just 11 goals in 50 games with Mario Lemieux and company.

Simmer spent the 1988-89 season getting hockey out of his system by playing in Germany. He later returned to North America, playing in parts of two seasons with the IHL's San Diego Gulls.

Simmer was a two time NHL All Star, and was also given the Bill Masterton trophy in 1986 for his dedication to the game. Despite so many injuries, Charlie always battled back.

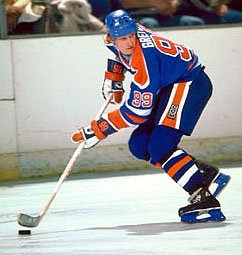

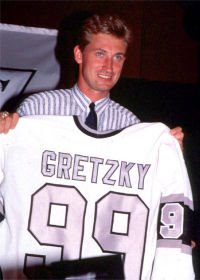

Luc Robitaille

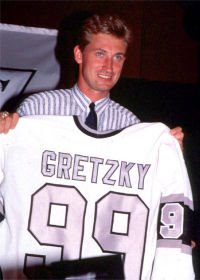

"Cool Hand Luc" Robitaille is one of the most popular athletes on the Hollywood sports scene ever. However when the Los Angeles Kings made Robitaille their ninth round pick (171st pick overall) of the 1984 NHL Entry draft, they didn't expect much from the left winger. The Kings got a bit "lucky" themselves when "Lucky Luc" Robitaille's career blossomed following his draft year.

"Cool Hand Luc" Robitaille is one of the most popular athletes on the Hollywood sports scene ever. However when the Los Angeles Kings made Robitaille their ninth round pick (171st pick overall) of the 1984 NHL Entry draft, they didn't expect much from the left winger. The Kings got a bit "lucky" themselves when "Lucky Luc" Robitaille's career blossomed following his draft year.Robitaille would be returned to junior hockey for the following two seasons where he dominated with the Quebec league's Hull Olympiques. In his magnificent junior career, Luc played in 197 games recording 155 goals, 270 assists for 425 points! 191 of those points came in his final season with Hull, a season in which he was named the Canadian Major Junior Player of the Year.

Doubts of his skating ability still plagued him but he managed to shake that reputation in 1987 as he won the Calder trophy as the National Hockey League's best rookie, outdistancing Flyers rookie goalie Ron Hextall in voting. He also was named to the NHL Second All Star Team in just his first year, scoring 45 times and totaling 84 points.

Doubts of his skating ability still plagued him but he managed to shake that reputation in 1987 as he won the Calder trophy as the National Hockey League's best rookie, outdistancing Flyers rookie goalie Ron Hextall in voting. He also was named to the NHL Second All Star Team in just his first year, scoring 45 times and totaling 84 points.Robitaille made up for any skating deficiencies with one of the most accurate shots in NHL history. He was a regular leader in shooting percentage, thanks to a number of reasons. He worked himself into high percentage scoring areas, often down low and in tight. Though a defender might have been draped all over him, he always kept his stick unchecked. He would release his shot in the blink of an eye, usually just burying passes and rebounds with no backswing at all.

There was no sophomore jinx for Lucky Luc, either, as he improved his performance in year 2 to 53 goals and 111 points and was named to the NHL's First All Star Team for the first of 4 times.

Robitaille's best season came in 1992-92 when he established NHL records for goals (63) and points (125) by a left winger and was named the Kings MVP as he elevated his game to the highest level as Wayne Gretzky missed half the season with a back injury. Robitaille also served as team captain during Gretzky's absence.

Robitaille, an under-noticed physical player, continued to be almost unquestioningly the league's best left winger for 8 seasons, consistently scoring goals. He scored at least 44 goals in 8 consecutive seasons (only Gretzky and Mike Bossy had better streaks), and also managed to shake his playoff jinx as he became a genuine playoff threat in 1992 with 12 goals in 12 games and in 1993 when he was a major part of the Kings "Cinderella" Cup run.

Just one year after coming so close to winning Lord Stanley's Grail, the Kings missed the playoffs. Robitaille played for Canada's national team at the 1994 World Championship in Italy. It was Robitaille who scored the gold medal winning goal in a shootout, giving Canada its first world championship in 33 years.

Back in Los Angeles changes were afoot following the disappointing playoff no-show. In the biggest trade of all, perhaps the most popular King of all time to Pittsburgh where he would join Mario Lemieux and the league's best collection of sharpshooters. However it wasn't meant to be in Pittsburgh. First Mario announced he wouldn't play that season to rest his ailing back, and then the NHL lock-out resulted in just a 48 game schedule. Luc managed 23 goals and 42 points, and despite scoring 7 times in 12 playoff games, he was dealt to the NY Rangers.

Robitaille's performance in the Big Apple dipped to average only 24 goals in his two seasons. Despite briefly being reunited with Wayne Gretzky, Robitaille wasn't used regularly because his style never really fit in with the Rangers. His lack of quickness was again becoming an issue as he got older.

At the beginning of the 1997 season, Luc was returned to the Los Angeles Kings where he is now a veteran counted on for leadership. With another injury riddled year, he scored only 16 times and many had written off Robitaille, which only proved to be a mistake.

Robitaille found his scoring touch again in 1998-99, lighting the lamp 39 times. He followed that up with seasons of 37 and 36 goals.

Robitaille found his scoring touch again in 1998-99, lighting the lamp 39 times. He followed that up with seasons of 37 and 36 goals.One of these goals stood out more than the others. He reached the 500-goal milestone in a game against the Buffalo Sabres on January 9, 1999. Only the sixth left winger in league history to reach the plateau, Robitaille scored the goal in his 928th NHL game, making him the 12th fastest ever to accomplish the feat.

In a surprise move, Robitaille became a un-restricted free agent and opted to sign with Detroit Red Wings in 2001. In his first season with the Wings, Robitaille registered 30 goals surpassing the 600-goal club and captured his first Stanley Cup and the Wings third cup in six years. Interestingly, with his day with the Stanley Cup, Robitaille brought the Cup back to Los Angeles, taking the trophy up into the hills by the famous "Hollywood" sign.

After two seasons and one Stanley Cup in Detroit, Robitaille was returned once again to the Los Angeles Kings for his third stint with the club in the summer of 2003. Luc Robitaille played his last game on April 17, 2006 with the Los Angeles Kings after 19 seasons of NHL competition.

With 557 of his 668 career NHL goals coming in a Los Angeles uniform he retired as the Kings all time leading goal scorer. He later became the fifth King to have his jersey #20 retired, joining Gretzky, Rogie Vachon, Marcel Dionne and Dave Taylor.

Kings Hockey Tickets

Marcel Dionne

Many of today's superstars of the professional sports world complain about a lack of privacy. The demands on their time because they are famous and worshipped by millions is probably the worst aspect of the life of a pro athlete.

Many of today's superstars of the professional sports world complain about a lack of privacy. The demands on their time because they are famous and worshipped by millions is probably the worst aspect of the life of a pro athlete.Rarely does a superstar slip through the cracks of prestige and recognition as inconspicuously as Marcel Dionne.

Dionne finished his career ranked as the third highest scorer of all time with 731 goals, 1040 assists and 1771 points in 1348 games. Only Wayne Gretzky and Gordie Howe amassed more impressive totals at the time.

In fact, of all the greats to grace the ice, Dionne ranks as the highest scoring French Canadian of all time. Not Guy Lafleur or Rocket Richard or Jean Beliveau or Mario Lemieux. Marcel Dionne outscored them all.

Yet when fans endlessly debate who is the greatest player of all time, Marcel's name hardly ever gets as much as a whisper. In the recent "Top 50 NHL Players of All Time" issue of the Hockey News, the third highest scorer in NHL history was ranked only 38th.

Why is Dionne under-appreciated? For one, he spent most of his career in Los Angeles when hockey was little more than an a passing thought in the sunbelt of the United States.

Another reason is despite all of his spectacular scoring displays, he has very little in terms of trophies in his display case. He was overshadowed first by the powerful Montreal Canadiens in the 1970s, and then by Wayne Gretzky in the 1980s.

Probably the biggest reason why Dionne gets very little acknowledgment as one of the game's greatest is because his own team never really achieved much in terms of team success. Dionne appeared in the Stanley Cup playoffs in only 9 of his 18 years, never once getting close to appearing in the Stanley Cup finals. He appeared in 49 games and managed 45 points. This lack of Stanley Cup success often equates to a diminished status when discussing the greatest ever.

Marcel Dionne was perhaps the first great French Canadian not to play for Montreal. Back then it was considered destiny for a high scoring French Canadian to play for the Habs. However the fates never allowed Dionne to fulfill his destiny. The 1971 draft was quite the mini-drama in itself as Montreal acquired the 1st overall pick, and were faced with the tough decision of selecting two French Canadian scoring stars - Dionne or Guy Lafleur.

Marcel Dionne was perhaps the first great French Canadian not to play for Montreal. Back then it was considered destiny for a high scoring French Canadian to play for the Habs. However the fates never allowed Dionne to fulfill his destiny. The 1971 draft was quite the mini-drama in itself as Montreal acquired the 1st overall pick, and were faced with the tough decision of selecting two French Canadian scoring stars - Dionne or Guy Lafleur.The Habs selected Lafleur, who initially struggled. Meanwhile Dionne went #2 to Detroit where he set the league on fire. Dionne, who was immediately dubbed "Little Beaver" because of his uncanny resemblance to a midget wrestler who used the stage name, set NHL rookie scoring records (since broken) and in fact scored 366 points in his first four seasons, more points in a four year period than any other player in history to that point.

Unfortunately he and the Wings had their differences, and after refusing to sign a contract he found the Los Angeles Kings were willing to pay $300,000 a season. That was the richest deal in hockey history to that point. A trade was worked out, and Dionne headed west.

Dionne instantly became the Kings shining jewel. Soon he would center one of the greatest lines in hockey history: the Triple Crown line with Dave Taylor and Charlie Simmer. His play on the ice was regal, winning the Art Ross and Lady Byng trophies.

Though Dionne's scoring prowess continued to impress on the California coast, he played in seemingly uninterrupted obscurity. Meanwhile Lafleur found his game, and was leading the Montreal Canadiens to multiple Stanley Cups.

Dionne would continue to play in Los Angeles until late 1987, when he accepted a trade to the New York Rangers. Dionne left, and continues to be, the Los Angeles Kings all time leading scorer. The Kings also retired his #16.

Dionne would continue to play in Los Angeles until late 1987, when he accepted a trade to the New York Rangers. Dionne left, and continues to be, the Los Angeles Kings all time leading scorer. The Kings also retired his #16.Dionne finished his career with the New York Rangers. Though he enjoyed his time on Broadway, his career came to a surprising end in the minor leagues. After being a healthy scratch many times in 1989, Dionne pushed for a minor league re-assignment, just wanting to play the game he loved. He would return to New York state and make it is home, opening up a dry cleaning business as well as promoting his own line of memorabilia.

Despite being one of the most prolific scorers in history, Dionne doesn't seem to get his due. Perhaps that's because he played in Los Angeles and never got the media attention he deserved. He never really played with a good team, as he was never part of a good playoff run or a Stanley Cup victory.

He is however, without a shadow of a doubt, one of the greatest hockey players of all time.

Mike Byers

Mike Byers was one of thousands of journeymen players in NHL history. Not too many of his 170 NHL or 291 WHA games were spectacular by any definition, but he did his job as well as anybody else.

Mike had a five year junior career for the Toronto Marlboros between 1962-67, where he won the Memorial Cup in 1967. He wasn't a big scorer but more of a streaky scorer. He had three four goal games and showed flashes of great hockey.

Mike was an effortless skater with a good burst of speed. He also had a very hard shot but for some reason didn't shoot enough. He played parts of two seasons for Toronto but mostly played in the minors. In 1969 he was traded to Philadelphia but only played 5 games for them late in the season. Mike didn't crack the Flyers lineup the following season (1969-70) and spent the entire season with the Quebec Aces (AHL).

Philadelphia lost their patience with Byers and shipped him to Los Angeles on May 21, 1970. He immediately caught on in LA and scored a fine 27 goals, leading the team, and 45 points, figures that he would never match again on this level. He played on the "Bee Line" together with Bob Berry and Juha Widing. They combined for 173 points and played very solidly. Mike himself had six two goal games and scored against every NHL team. During that season many observers ranked Mike as having one of the best backhanded shots in the league.

The next season Mike came struggling out of the gate and only scored 9 points in the first 28 games for Los Angeles. He was promptly traded to Buffalo. He finished the season in Buffalo and scored 16 points in 46 games and actually played on a line together with Rick Martin and Gilbert Perreault for a brief period. Unfortunately Mike and Sabres coach Joe Crozier didn't get along very well.

"I loved Punch Imlach, both as a coach and general manager," said Mike, "But I didn't have a lot of respect for Joe Crozier, who was coaching the Sabres at the time (1972). I never saw eye-to-eye with Joe. And what I was looking to in Buffalo was a full year with Joe as coach. I just didn't see a lot of positive things by staying in Buffalo. So I jumped."

Mike jumped to the newly started rival league WHA. He had been selected by the Los Angeles Sharks in the 1972 WHA general player draft on February 12, 1972. Unfortunately for Mike there wasn't much to cheer about in LA.

"I wasn't really impressed with their management (LA Sharks) right from the beginning," recalled Mike. " I found out later that many of the people who ran the Sharks had never been involved with hockey before. I found out very quickly, their practice session times were scheduled very poorly. So were their travel schedules. And their philosophy was to put out a team on the ice that would be like the Broad Street Bullies in Philadelphia. The best thing that ever happened to me as a member of the Sharks was the day they traded me to the Whalers. It was like going from rags to riches."

After 56 games in Los Angeles (19 goals, 36 points) Mike was traded to the New England Whalers for Mike Hyndman. He scored another 6 goals for New England that season, finishing with a respectable 25 goals. The following two seasons Mike scored 29 goals, 50 points and 22 goals, 48 points for New England.

Mike was then signed as a free agent by Cincinnati early in 1976. He played there briefly before playing his last season in 1976-77 for the Rochester Americans (AHL).

Mike retired and moved to Los Angeles where he became a senior vice-president for a bank and investment company.

In 166 NHL games, he had 42 goals and 34 assists. In 263 WHA games, he had 83 goals and 74 assists.

Mike had a five year junior career for the Toronto Marlboros between 1962-67, where he won the Memorial Cup in 1967. He wasn't a big scorer but more of a streaky scorer. He had three four goal games and showed flashes of great hockey.

Mike was an effortless skater with a good burst of speed. He also had a very hard shot but for some reason didn't shoot enough. He played parts of two seasons for Toronto but mostly played in the minors. In 1969 he was traded to Philadelphia but only played 5 games for them late in the season. Mike didn't crack the Flyers lineup the following season (1969-70) and spent the entire season with the Quebec Aces (AHL).

Philadelphia lost their patience with Byers and shipped him to Los Angeles on May 21, 1970. He immediately caught on in LA and scored a fine 27 goals, leading the team, and 45 points, figures that he would never match again on this level. He played on the "Bee Line" together with Bob Berry and Juha Widing. They combined for 173 points and played very solidly. Mike himself had six two goal games and scored against every NHL team. During that season many observers ranked Mike as having one of the best backhanded shots in the league.

The next season Mike came struggling out of the gate and only scored 9 points in the first 28 games for Los Angeles. He was promptly traded to Buffalo. He finished the season in Buffalo and scored 16 points in 46 games and actually played on a line together with Rick Martin and Gilbert Perreault for a brief period. Unfortunately Mike and Sabres coach Joe Crozier didn't get along very well.

"I loved Punch Imlach, both as a coach and general manager," said Mike, "But I didn't have a lot of respect for Joe Crozier, who was coaching the Sabres at the time (1972). I never saw eye-to-eye with Joe. And what I was looking to in Buffalo was a full year with Joe as coach. I just didn't see a lot of positive things by staying in Buffalo. So I jumped."

Mike jumped to the newly started rival league WHA. He had been selected by the Los Angeles Sharks in the 1972 WHA general player draft on February 12, 1972. Unfortunately for Mike there wasn't much to cheer about in LA.

"I wasn't really impressed with their management (LA Sharks) right from the beginning," recalled Mike. " I found out later that many of the people who ran the Sharks had never been involved with hockey before. I found out very quickly, their practice session times were scheduled very poorly. So were their travel schedules. And their philosophy was to put out a team on the ice that would be like the Broad Street Bullies in Philadelphia. The best thing that ever happened to me as a member of the Sharks was the day they traded me to the Whalers. It was like going from rags to riches."

After 56 games in Los Angeles (19 goals, 36 points) Mike was traded to the New England Whalers for Mike Hyndman. He scored another 6 goals for New England that season, finishing with a respectable 25 goals. The following two seasons Mike scored 29 goals, 50 points and 22 goals, 48 points for New England.

Mike was then signed as a free agent by Cincinnati early in 1976. He played there briefly before playing his last season in 1976-77 for the Rochester Americans (AHL).

Mike retired and moved to Los Angeles where he became a senior vice-president for a bank and investment company.

In 166 NHL games, he had 42 goals and 34 assists. In 263 WHA games, he had 83 goals and 74 assists.

Darryl Sydor

I always had high hopes for Darryl Sydor. He was a great junior player in Kamloops (where he patrolled the blue line with Scott Niedermayer). He showed a lot of offensive promise, and when he joined Wayne Gretzky's Los Angeles Kings to start his career in 1991 I kept a close eye on him.

And he went on to a great career. The two-time Stanley Cup champion (Dallas 1999 and Tampa Bay 2004) and had 507 points (98+409) in 1,291 career NHL games.He added another 9 goals and 56 points in 155 Stanley Cup playoff games.

He was such a great skater, blessed with balance and agility and amazing lateral movement. He accelerated well and jumped into the attack smartly. He made strong outlet passes and could rush the puck out of the zone, though usually just to the center line to dump it in.

I guess with his skating ability and junior numbers I had hoped for more offense from Sydor. He did emerge into a very solid two way defender, especially in Dallas, but in Los Angeles, like most young defensemen, he needed some sheltering as he needed time to mature physical and defensively.

Though he challenged the 50 point mark a few times in Dallas, Sydor will not be remembered as a top offensive defenseman but as a really solid, all around blue liner who offered a little of everything to his team.

Sydor, who also had stints in Columbus, Tampa, Pittsburgh and St. Louis, is quick to credit his mentors for his longevity in the NHL.

“I have been able to learn under players like Charlie Huddy, Craig Ludwig, Guy Carbonneau and Mike Keane,” he said. “I learned from Charlie in LA and these other guys in Dallas where I took a lot of learning experiences from and then I’ve been thrown into some situations where I have been able to take my game to the next level. Now, being an experienced defenseman, you’re relied on a lot more in important situations.”

And he went on to a great career. The two-time Stanley Cup champion (Dallas 1999 and Tampa Bay 2004) and had 507 points (98+409) in 1,291 career NHL games.He added another 9 goals and 56 points in 155 Stanley Cup playoff games.

He was such a great skater, blessed with balance and agility and amazing lateral movement. He accelerated well and jumped into the attack smartly. He made strong outlet passes and could rush the puck out of the zone, though usually just to the center line to dump it in.

I guess with his skating ability and junior numbers I had hoped for more offense from Sydor. He did emerge into a very solid two way defender, especially in Dallas, but in Los Angeles, like most young defensemen, he needed some sheltering as he needed time to mature physical and defensively.

Though he challenged the 50 point mark a few times in Dallas, Sydor will not be remembered as a top offensive defenseman but as a really solid, all around blue liner who offered a little of everything to his team.

Sydor, who also had stints in Columbus, Tampa, Pittsburgh and St. Louis, is quick to credit his mentors for his longevity in the NHL.

“I have been able to learn under players like Charlie Huddy, Craig Ludwig, Guy Carbonneau and Mike Keane,” he said. “I learned from Charlie in LA and these other guys in Dallas where I took a lot of learning experiences from and then I’ve been thrown into some situations where I have been able to take my game to the next level. Now, being an experienced defenseman, you’re relied on a lot more in important situations.”

Jay Wells

Jay Wells was a junior standout with the Kingston Canadiens from 1976 through 1979. It wasn't flashy skill or scoring exploits that made him the 16th overall draft pick in the NHL's deepest amateur draft (1979) but rather his reputation as a mean and aggressive defenseman. Jay was able to work on that reputation throughout almost 1100 NHL games.

Jay was drafted by the Los Angeles Kings, and he would apply his trade for 9 seasons in the warm California sunshine. During the 1980s the Kings weren't exactly setting the league on fire, and often solid players like Wells weren't given much attention. But he became a coveted defenseman by all teams in the NHL. Often other teams would inquire about Well's availability, but the Kings were smart to hang on to their leader.

Every team in the NHL wanted Jay because he was one of the best in the entire circuit at clearing the front of the net. He was an excellent body checker, and a willing fighter. Jay was also recognized as one of the better shot blocking defensemen. It was said the only things stronger than his arms and legs were his work ethic and character. While he didn't possess great offensive skills, he had decent agility and usually made an intelligent clearing pass to get the Kings out of trouble in their own zone. He was at his best when he played within his limits and didn't over extend himself.

After 9 years in Los Angeles, Jay was traded to the Philadelphia Flyers in 1988. That trade happened only a month or so after the Kings had acquired Wayne Gretzky. While it was disappointing for Jay not to get a chance to play with Wayne, he brought his hard working style to the more physical east coast and settled in nicely.

Jay would spend 2 seasons in Philly before a late trade in March 1990 took him to Buffalo. The veteran experience Jay brought to the Sabres was his biggest asset at this stage of his career. He continued to play his rock-hard style of hockey, but struggled with injuries. He played in just 85 games over parts of three seasons in Buffalo. Lat in the 1991-92 season was traded to the New York Rangers for a similar defenseman in Randy Moller.

Jay enjoyed his time in New York. He spent 4 seasons there, none more memorable than the 1993-94 season. Jay played in 79 games games that season, his first fully healthy season in 7 seasons. He also participated in 23 playoff games as the New York Rangers battled the Vancouver Canucks in a memorable battle for the Stanley Cup. The Rangers ultimately won the championship. For Jay, like all hockey players, it was the highlight of his career. All the years of blood, sweat and injuries finally were rewarded for Jay and his Rangers teammates. When Jay had his opportunity to lift the Cup above his head, he said "I had no idea what to do with it."

Jay continued to play in the NHL until 1997, with stops in St. Louis and Tampa Bay, before he opted to step off the ice and behind the bench.

He played in 1098 NHL games, scoring 47 goals and 263 points, while earning 2359 minutes in the penalty box. He is one of hockey's true warriors, and deserves to be remembered as such.

Jay was drafted by the Los Angeles Kings, and he would apply his trade for 9 seasons in the warm California sunshine. During the 1980s the Kings weren't exactly setting the league on fire, and often solid players like Wells weren't given much attention. But he became a coveted defenseman by all teams in the NHL. Often other teams would inquire about Well's availability, but the Kings were smart to hang on to their leader.

Every team in the NHL wanted Jay because he was one of the best in the entire circuit at clearing the front of the net. He was an excellent body checker, and a willing fighter. Jay was also recognized as one of the better shot blocking defensemen. It was said the only things stronger than his arms and legs were his work ethic and character. While he didn't possess great offensive skills, he had decent agility and usually made an intelligent clearing pass to get the Kings out of trouble in their own zone. He was at his best when he played within his limits and didn't over extend himself.

After 9 years in Los Angeles, Jay was traded to the Philadelphia Flyers in 1988. That trade happened only a month or so after the Kings had acquired Wayne Gretzky. While it was disappointing for Jay not to get a chance to play with Wayne, he brought his hard working style to the more physical east coast and settled in nicely.

Jay would spend 2 seasons in Philly before a late trade in March 1990 took him to Buffalo. The veteran experience Jay brought to the Sabres was his biggest asset at this stage of his career. He continued to play his rock-hard style of hockey, but struggled with injuries. He played in just 85 games over parts of three seasons in Buffalo. Lat in the 1991-92 season was traded to the New York Rangers for a similar defenseman in Randy Moller.

Jay enjoyed his time in New York. He spent 4 seasons there, none more memorable than the 1993-94 season. Jay played in 79 games games that season, his first fully healthy season in 7 seasons. He also participated in 23 playoff games as the New York Rangers battled the Vancouver Canucks in a memorable battle for the Stanley Cup. The Rangers ultimately won the championship. For Jay, like all hockey players, it was the highlight of his career. All the years of blood, sweat and injuries finally were rewarded for Jay and his Rangers teammates. When Jay had his opportunity to lift the Cup above his head, he said "I had no idea what to do with it."

Jay continued to play in the NHL until 1997, with stops in St. Louis and Tampa Bay, before he opted to step off the ice and behind the bench.

He played in 1098 NHL games, scoring 47 goals and 263 points, while earning 2359 minutes in the penalty box. He is one of hockey's true warriors, and deserves to be remembered as such.

Robb Stauber

Robb "Rusty" Stauber was born in Duluth, Minnesota. It was in Minnesota where Robb emerged as an NHL prospect. After he graduated from high school he went on to the University of Minnesota where he set school records for career games played, minutes played and wins by a goaltender. His highlight of his amateur career came in 1987-88. Based on a 34-100 season with 5 shutouts and a 2.72 goals against average, Robb became the first goaltender to win the Hobey Baker award as the top player in United States college hockey!

Robb, who was drafted by the Los Angeles Kings 107th overall back in 1986, turned professional in 1989. He would appear in 2 games with the Kings in 1989-90. Otherwise Robb was buried in the minor leagues until 1992-93.

In that season Robb emerged as an NHL story. The rookie went undefeated in his first 10 starts that season (9-0-1), including a 7 game consecutive winning streak. Robb, who was Kelly Hrudey's back up that season, ended with a 15-8-4 record, and posted another 3 big wins in 4 playoff games as he helped Wayne Gretzky and the Kings go all the way to the Stanley Cup finals. Robb calls that moment his greatest in his hockey career.

Robb's fortunes went downhill quickly the following season, as did the Kings'. Robb struggled through a 4-11-5 season. He did pick up his first and only NHL shutout in a rare 0-0 tie against Dallas.

The Buffalo Sabres were hoping to resurrect Robb's career when they acquired him during the lockout shortened season of 1994-95. Robb was involved in the huge trade which saw Robb, Alexei Zhitnik, Charlie Huddy and a draft pick come to Buffalo in exchange for Phillippe Boucher, Denis Tsygurov and Grant Fuhr. Robb played in 6 games for the Sabres in the 48 game condensed schedule. However because of the emergence of Dominik Hasek, Robb rarely got a chance to play.

That proved to be Robb's final season in the NHL. He played the 1995-96 season with the Sabres farm team in Rochester, where the highlight of his season was when he scored a goal on October 9, 1995. He would sign with the Washington Capitals and New York Rangers over the following 2 seasons, but spent the entire seasons in the minor leagues. He rounded out his career with a short stint with the independant Manitoba Moose.

Upon retirement, Robb returned to Minnesota where he is a goaltending consultant at his old stomping grounds at the University of Minnesota. He also invented the Staubar Trainer which is a device goalies wear in practice which restricts the goalies ability to rely on reflexes or athleticism with the idea being forces the goalie to learn the fundamentals of playing angles and using the bulk of his body to get in the way of the puck.

Robb, who was drafted by the Los Angeles Kings 107th overall back in 1986, turned professional in 1989. He would appear in 2 games with the Kings in 1989-90. Otherwise Robb was buried in the minor leagues until 1992-93.

In that season Robb emerged as an NHL story. The rookie went undefeated in his first 10 starts that season (9-0-1), including a 7 game consecutive winning streak. Robb, who was Kelly Hrudey's back up that season, ended with a 15-8-4 record, and posted another 3 big wins in 4 playoff games as he helped Wayne Gretzky and the Kings go all the way to the Stanley Cup finals. Robb calls that moment his greatest in his hockey career.

Robb's fortunes went downhill quickly the following season, as did the Kings'. Robb struggled through a 4-11-5 season. He did pick up his first and only NHL shutout in a rare 0-0 tie against Dallas.

The Buffalo Sabres were hoping to resurrect Robb's career when they acquired him during the lockout shortened season of 1994-95. Robb was involved in the huge trade which saw Robb, Alexei Zhitnik, Charlie Huddy and a draft pick come to Buffalo in exchange for Phillippe Boucher, Denis Tsygurov and Grant Fuhr. Robb played in 6 games for the Sabres in the 48 game condensed schedule. However because of the emergence of Dominik Hasek, Robb rarely got a chance to play.

That proved to be Robb's final season in the NHL. He played the 1995-96 season with the Sabres farm team in Rochester, where the highlight of his season was when he scored a goal on October 9, 1995. He would sign with the Washington Capitals and New York Rangers over the following 2 seasons, but spent the entire seasons in the minor leagues. He rounded out his career with a short stint with the independant Manitoba Moose.

Upon retirement, Robb returned to Minnesota where he is a goaltending consultant at his old stomping grounds at the University of Minnesota. He also invented the Staubar Trainer which is a device goalies wear in practice which restricts the goalies ability to rely on reflexes or athleticism with the idea being forces the goalie to learn the fundamentals of playing angles and using the bulk of his body to get in the way of the puck.

Randy Holt

Randy Holt was a mad man of the ice. He still holds the record for most penalty minutes (67) assessed in a single game. Angered by a cheap shot by Philadelphia's Ken Linseman, Randy set off on a rampage that ignited a bench clearing brawl.

Thanks to YouTube, here's the footage of that record breaking night:

In total that game (actually, it was all just in the first period!) Holt was assessed a record 9 penalties - one minor, three majors, two 10-minute misconducts and three game misconducts. That all totaled to 67 PIMs - the only player to be assessed more PIMs than there are actually minutes in a game!

Not surprisngly, Holt was also suspended for three games.

In 395 NHL games, Holt scored just 4 goals and 37 assists, and amassed 1,438 penalty minutes. The 1970s was hockey's goon era, and Randy's reputation kept him in the league.

After leaving the ice Holt went into the car sales business. He also had a couple of unfortunate car accidents, including being hit by a truck while walking at an intersection. That injury resulted in severe head trauma.

Thanks to YouTube, here's the footage of that record breaking night:

In total that game (actually, it was all just in the first period!) Holt was assessed a record 9 penalties - one minor, three majors, two 10-minute misconducts and three game misconducts. That all totaled to 67 PIMs - the only player to be assessed more PIMs than there are actually minutes in a game!

Not surprisngly, Holt was also suspended for three games.

In 395 NHL games, Holt scored just 4 goals and 37 assists, and amassed 1,438 penalty minutes. The 1970s was hockey's goon era, and Randy's reputation kept him in the league.

After leaving the ice Holt went into the car sales business. He also had a couple of unfortunate car accidents, including being hit by a truck while walking at an intersection. That injury resulted in severe head trauma.

Rick Knickle

Patience, patience, patience....It took Rick 14-years of minor league hockey before he saw his first NHL action. He had played for 12 different pro teams before finally being called up by the Los Angeles Kings late during the 1992-93 season.

Why did it take such a long time for Rick before he finally got his chance to play in the NHL? Probably because of bad timing. Rick had a stellar career in the juniors while playing for the Brandon Wheat Kings (WHL). During his three years there (1977-80) Rick was 71-22-16 with a 3.83 GAA and was a 1st team All-Star in 1979. Compared to his successor in Brandon, Ron Hextall who had a 54-54-2 record and a 5.16 GAA one would think that it was Rick who would have the advantage. But it was Hextall who got the lucky break, not Rick.

Rick made a career of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was drafted 116th overall in 1979 by Buffalo and was sent down to Rochester (AHL). There he shared the goaltending duties with veteran Phil Myre, who got the callup when there were injuries. The other one who used to get called up was Jacques Cloutier, drafted the same year as Rick (55th overall). Buffalo at that time had Don Edwards, Tom Barrasso and Bob Sauve. On top of that Barrasso won the Vezina trophy in 1984-85, so their goalkeeping was stellar.

In the meantime Ron Hextall who had a much worse junior career was playing in Philadelphia He got the chance mainly due to Pelle Lindbergh's tragic death. Reducing the depth chart on the Flyers team considerably and giving him the break he needed.

Rick admitted that he was pretty bitter about his situation at one time.

"I felt I wasn't getting a fair shake, but as I was getting older I went to the rink in a better frame of mind."

Rick didn't blame anybody for failing to make the Sabres team.

"I didn't play the way I was capable of playing. In junior I was playing 50 games, I was always the No 1 goalie. It's a whole different situation, when you're a young kid, to deal with not playing as much. If I could go back there and have the same frame of mind as I do right now, it'd be a lot different." Rick said.

After Rick's contract with Buffalo expired he signed with Montreal (February 8,1985). Once again Rick came to a team stacked with good goaltenders. Montreal had a certain Patrick Roy. As well as Steve Penney. When Penney was traded for Brian Hayward, it was time for Rick to move again.

"I never got the chance to show that I could play in Montreal. I never got a chance to play in the odd game, to get someone to say, 'Hey, he can play, let's re-evaluate things.' Every year with Montreal when I went to training camp, they sent me right down. I'm not a training-camp goalie. I never have been. You know, that shouldn't hold a lot of water. Sometimes it takes you a while to get into a groove. I think I'm the type of goalie (who), the more you see me, the more I play, the better I get," Rick said.

Rick was a typical stand-up goalie with good reflexes. His biggest weakness was probably that he didn't challenge the shooters enough. Rick didn't just play in the AHL but spend most of the time in the IHL (15 seasons). He was a four time All-Star in the IHL (two 1st and two 2nd team selections). Rick also won the James Norris memorial trophy (fewest goals against in the IHL) in 1989 & 93.

Patience however pays off. As a property of Los Angeles Kings,Rick got the callup to the NHL for the first time as a 33-year old in 1993 as some of the Los Angeles goalies went down with injuries. Rick played 10 games for LA,doing pretty well as he won 6 games, posting a 3.95 GAA. The following season (1993-94) Rick played 4 games for LA with a 3.10 GAA.

That was it for him in terms of NHL action,but at least he got there after so many years. Had he gotpicked by another team then he might very well have had a pretty good NHL career. After Rick's final NHL appearance in 1994, he played another couple of seasons in the IHL before retiring as a 37-year old in 1997.

Why did it take such a long time for Rick before he finally got his chance to play in the NHL? Probably because of bad timing. Rick had a stellar career in the juniors while playing for the Brandon Wheat Kings (WHL). During his three years there (1977-80) Rick was 71-22-16 with a 3.83 GAA and was a 1st team All-Star in 1979. Compared to his successor in Brandon, Ron Hextall who had a 54-54-2 record and a 5.16 GAA one would think that it was Rick who would have the advantage. But it was Hextall who got the lucky break, not Rick.

Rick made a career of being in the wrong place at the wrong time. He was drafted 116th overall in 1979 by Buffalo and was sent down to Rochester (AHL). There he shared the goaltending duties with veteran Phil Myre, who got the callup when there were injuries. The other one who used to get called up was Jacques Cloutier, drafted the same year as Rick (55th overall). Buffalo at that time had Don Edwards, Tom Barrasso and Bob Sauve. On top of that Barrasso won the Vezina trophy in 1984-85, so their goalkeeping was stellar.

In the meantime Ron Hextall who had a much worse junior career was playing in Philadelphia He got the chance mainly due to Pelle Lindbergh's tragic death. Reducing the depth chart on the Flyers team considerably and giving him the break he needed.

Rick admitted that he was pretty bitter about his situation at one time.

"I felt I wasn't getting a fair shake, but as I was getting older I went to the rink in a better frame of mind."

Rick didn't blame anybody for failing to make the Sabres team.

"I didn't play the way I was capable of playing. In junior I was playing 50 games, I was always the No 1 goalie. It's a whole different situation, when you're a young kid, to deal with not playing as much. If I could go back there and have the same frame of mind as I do right now, it'd be a lot different." Rick said.

After Rick's contract with Buffalo expired he signed with Montreal (February 8,1985). Once again Rick came to a team stacked with good goaltenders. Montreal had a certain Patrick Roy. As well as Steve Penney. When Penney was traded for Brian Hayward, it was time for Rick to move again.

"I never got the chance to show that I could play in Montreal. I never got a chance to play in the odd game, to get someone to say, 'Hey, he can play, let's re-evaluate things.' Every year with Montreal when I went to training camp, they sent me right down. I'm not a training-camp goalie. I never have been. You know, that shouldn't hold a lot of water. Sometimes it takes you a while to get into a groove. I think I'm the type of goalie (who), the more you see me, the more I play, the better I get," Rick said.

Rick was a typical stand-up goalie with good reflexes. His biggest weakness was probably that he didn't challenge the shooters enough. Rick didn't just play in the AHL but spend most of the time in the IHL (15 seasons). He was a four time All-Star in the IHL (two 1st and two 2nd team selections). Rick also won the James Norris memorial trophy (fewest goals against in the IHL) in 1989 & 93.

Patience however pays off. As a property of Los Angeles Kings,Rick got the callup to the NHL for the first time as a 33-year old in 1993 as some of the Los Angeles goalies went down with injuries. Rick played 10 games for LA,doing pretty well as he won 6 games, posting a 3.95 GAA. The following season (1993-94) Rick played 4 games for LA with a 3.10 GAA.

That was it for him in terms of NHL action,but at least he got there after so many years. Had he gotpicked by another team then he might very well have had a pretty good NHL career. After Rick's final NHL appearance in 1994, he played another couple of seasons in the IHL before retiring as a 37-year old in 1997.

Dennis Abgrall

Dennis Abgrall of Moosomin, Saskatchewan was a star right winger with the Saskatoon Blades in the early 1970s. That helped him get drafted by both the Los Angeles Kings (70th overall in 1973) and the Los Angeles Blades of the WHA (1972 general player draft). But a Hollywood career was not in the cards for young Abgrall.

Dennis Abgrall of Moosomin, Saskatchewan was a star right winger with the Saskatoon Blades in the early 1970s. That helped him get drafted by both the Los Angeles Kings (70th overall in 1973) and the Los Angeles Blades of the WHA (1972 general player draft). But a Hollywood career was not in the cards for young Abgrall.Abgrall initially followed his dream and was devoted to making the National Hockey League. He signed with Kings and reported to their farm team for two years. He even got called up for 13 games during the 1975-76 seasons, picking up 2 assists.

Sensing his future with the Kings was perhaps not what he had hoped for, Abgrall jumped at the chance to sign with the WHA's Cincinnati Stingers, the team that absorbed his WHA rights after the LA Sharks went belly up. He enjoyed two years of big league hockey in the WHA, and he also enjoyed the sizeable pay increase.

When the WHA folded Abgrall headed overseas, playing for teams in Germany, Belgium and the Netherlands.

Skip Krake

A sensational junior star with the Estevan Bruins, North Battleford, Saskatchewan's Skip Krake (he was born at tiny Rabbit Lake) was a solid utility player for three NHL teams between 1963-64 and 1970-71, and with 2 WHA teams until 1976. The diminutive Krake was too small to be an offensive star in the NHL, but made a good career for himself by specializing as a strong defensive center.

Having grown up in the Boston Bruins system, Krake was disappointed to leave Estevan and head to the minor leagues. But he gained valuable experience by playing with Minneapolis and Oklahoma City in the CHL. He also participated in 19 games over 4 seasons with the Bruins.

By 1967-68 Krake finally made the Bruins, thanks largely to NHL expansion. The NHL doubled in size from six to twelve teams. Krake was not selected by an expansion team, but was able to move up and fill a hole on the Bruins roster created by players who did depart. Krake played in 68 games, scoring 5 goals and 12 points in limited ice time..

On May 20, 1968, the Bruins traded Krake to the L.A. for a first round draft choice that was used to claim a high-scoring junior winger named Reggie Leach. Krake split the 1968-69 season between the Kings and Springfield of the AHL, but was a full time NHLer by the 1969-70 season.

Krake's time in the Californian sunshine came to an end when he was claimed by the Buffalo Sabres in the NHL Expansion Draft of 1970. Krake played admirably in 74 games in their inaugural season, scoring 4 goals and 9 points.

The Sabres were looking to free up roster space for younger players the following year, so Krake searched for work in the professional WHL with Salt Lake in 1971-72. He then moved to Cleveland for 3 seasons, playing with the WHA crusaders before one final season with the WHA Edmonton Oilers.

After scoring 51 points in 53 games as the captain of the Salt Lake Golden Eagles, Krake was selected by the Cleveland Crusaders in the WHA General Player Draft. He played three seasons in Cleveland and one with the Edmonton Oilers before retiring in 1976.

After retiring Krake moved to Lloydminister, Saskatchewan where he has been involved in several retail operations, including a sporting goods store and Fountain Tire franchise.

Denis Tsygurov

Denis Tsygurov, born in Chelyabinsk, Russia on February 26th, 1971, was once a highly praised prospect in the Buffalo Sabres organization. Unfortunately he was never able to fulfill that promise.

Denis, the son of Russian hockey coach Genady Tsygurov, was the Buffalo Sabres first selection in the 1993 NHL entry draft, however the pick came in the second round, 38th overall. Regardless, Denis was much touted by the Sabres. They raved about his size - 6'3" and 200 pounds - plus his mobility. He was regarded as more of a defensive defenseman, but had good enough puck skills to start a rush.

Injuries would wreak havoc on the promising career of this Russian defenseman however. In his first year in North American he got into only 32 games total - and only 8 in the NHL. He would make the Sabres straight out of training camp during the lockout shortened 1994-95 season, but only 4 games into the season he found himself traded to the Los Angeles Kings in a huge trade. Denis accompanied Phillippe Boucher and Grant Fuhr to California in exchange for Alexei Zhitnik, Charlie Huddy, Robb Stauber and a draft pick. Denis would finish the season with the Kings, but only got into 21 games thanks to nagging injuries. Denis failed to register a point in that time.

Injuries continued to plague Denis in 1995-96. He only played in 18 games with the Kings (scoring his only NHL goal plus 5 assists) but spent as much time in the minor leagues. By the end of the year he returned to his native Russia.

Denis spent the 1996-97 season in Europe, splitting the season between Russia and the Czech Republic. He attempted a comeback to North American hockey in 1997-98 with 15 games with the Long Beach Ice Dogs of the fledgling International Hockey League. However that venture proved to be unfruitful. He spent the rest of the season in Finland.

Although his NHL days were well behind him, Denis continued to play in Russia until the next century.

Denis played a total of 51 games in the NHL, scoring 1 goal and 5 assists.

Denis, the son of Russian hockey coach Genady Tsygurov, was the Buffalo Sabres first selection in the 1993 NHL entry draft, however the pick came in the second round, 38th overall. Regardless, Denis was much touted by the Sabres. They raved about his size - 6'3" and 200 pounds - plus his mobility. He was regarded as more of a defensive defenseman, but had good enough puck skills to start a rush.

Injuries would wreak havoc on the promising career of this Russian defenseman however. In his first year in North American he got into only 32 games total - and only 8 in the NHL. He would make the Sabres straight out of training camp during the lockout shortened 1994-95 season, but only 4 games into the season he found himself traded to the Los Angeles Kings in a huge trade. Denis accompanied Phillippe Boucher and Grant Fuhr to California in exchange for Alexei Zhitnik, Charlie Huddy, Robb Stauber and a draft pick. Denis would finish the season with the Kings, but only got into 21 games thanks to nagging injuries. Denis failed to register a point in that time.

Injuries continued to plague Denis in 1995-96. He only played in 18 games with the Kings (scoring his only NHL goal plus 5 assists) but spent as much time in the minor leagues. By the end of the year he returned to his native Russia.

Denis spent the 1996-97 season in Europe, splitting the season between Russia and the Czech Republic. He attempted a comeback to North American hockey in 1997-98 with 15 games with the Long Beach Ice Dogs of the fledgling International Hockey League. However that venture proved to be unfruitful. He spent the rest of the season in Finland.

Although his NHL days were well behind him, Denis continued to play in Russia until the next century.

Denis played a total of 51 games in the NHL, scoring 1 goal and 5 assists.

Victor Netchaev

"Victor who?" you are probably ask yourself right about now. But he is the answer to the popular trivia question "who was the first Soviet trained player to play in the National Hockey League?" Nice job if you thought it was Sergei Priakhin, who was the first Soviet trained player who was given permission to play in the NHL, but Mr. Netchaev actually him beat by 7 years.

Netchaev, a center, only played in 3 NHL games during his career, so it is easy to see how he is barely a footnote in history. These three games went to the history books though, because Victor was the first Soviet trained player to appear in the NHL, as well as the first to score a goal.

European hockey history expert Patrick Houda tells us more.

"Victor made his North American debut as a 27-year old in 1982 for New Haven in the AHL. He was off to a fast start in New Haven and scored 1 goal and 5 points in his first 4 games there. It was his 1 goal and 2 assist performance in a game vs. Adirondack that gave him the call up to Los Angeles Kings.

The historic date for his NHL debut was October 16, 1982 when he appeared in a Los Angeles Kings uniform. The game was vs. the New York Islanders at Nassau Coliseum.

"Netchaev was put on a line together with Darryl Evans and Steve Bozek. Kings lost the game 1-4 and Victor was held pointless in the game, but his performance was solid."

"The next night at Madison Square Garden, Victor beat Rangers goalie Steve Weeks 17:15 into the 1st period to make it 3-0 Los Angeles. His goal came on an assist by Darryl Evans and was the first ever goal in the NHL by a Russian trained player. Los Angeles went on to win 4-2 and Victor was one of the best players on the ice, having 5 shots on goal and being +1," says Houda.

"He only played sparingly in his third and last NHL game and was then sent down back to New Haven for conditioning purposes, as GM George Maguire put it."

Victor's son Greg offers more input on his father's career:

"My father was actually offered a contract by the Kings for 2 years plus one option. But he did not want to stay with the Kings for 2 years for fear of being moved down to the minor league. He actually just wanted a shorter term of time which would eliminate the probability of going down to the minor because of age (27). The third "game" at Forum, in Los Angeles against the New Jersey Devils, was the beginning of "North American" negotiations for a contract. During these negotiations he was stripped of his gear, forbidden to see, play, or practice with his team, and was almost metaphorically "jailed" for almost a month. "

"Being from the USSR, he was totally shocked by the lack of care or respect or even understanding of the needs of the player himself in the pro sports here. It seemed to him that money was first and this whole dilemma had nothing to do with the sport anymore. He also said that "It was very hard to work with the manager (George Maguire) who had busy hands, one hand with whiskey and one with a cigarette."

Although Netchaev had NHL offers from other teams (New York Rangers, Hartford Whalers), he opted to briefly play in West Germany with Dusseldorf.

But how did Netchaev escape the Soviet Union and come to play in the NHL? Houda gives us a look into Netchaev's background.

"He was born in Kuibyshevka-Vostochnaya in Siberia, Russia on January 28, 1955. He made his debut in the Russian elite league as a 17-year old for Spartak and had 16 pts (8 goals + 8 assists) in 20 games.

"The next season (1974-75) he played in the 2nd division for his home team Siberia where he had a fine season with 20 goals (32 pts) in 56 games. After that he got picked by SKA Leningrad in the Russian elite league where he played between 1975-80. During the 1980-81 season he split his time in two 2nd division clubs, Binokor and Izhstal where he scored 40 points (26 goals and 14 assists) in 40 games.

"That was Victor's last season in Russia. He met an American woman who he married and moved to USA, which made him miss the entire 1981-82 season."

The American woman with whom he fell in love with was Cheryl Haigler, a Yale graduate student studying abroad in Leningrad. They actually met in Switzerland in 1977, when Netchaev was playing in the Spengler Cup. They married in 1980 but she was forced to return to the United States because her visa expired shortly after the wedding. She took a job in Boston with an accounting firm, and began the two year legal process of freeing Netchaev to come to America.

The Kings got word of his arrival in America, and even though he was far from a top Soviet player they were immediately interested. He got drafted in 1982 by Los Angeles in the 7th round, 132nd overall.

What has Netchaev been up to since hanging up the blades. Son Greg fills us in on that:

" Since he left the ice, he was doing numerous things involving entertainment, managing, local television programs (russian), radioing (russian). Then, starting from 1991, he began working as a manager and director of development of players with his partner Serge Levin in ARTV Sports Management. From '92-94 he was also the assistant coach and international scout of the Milwaukee Admirals. He still works in ARTV Sports Management as his main business."

Victor scored 137 goals 234 points in 328 Russian league games and 4 goals and 11 points in 28 AHL games.

His NHL stats were nothing too impressive with 1 goal in 3 games, with a +1 rating and 7 shots on goal. But it was that first game and first goal that today is the trivia question. Who was the first Soviet trained player to score a goal in the NHL ? Not Fetisov, not Makarov, not Mogilny, not Bure, but a guy from Siberia named Victor Netchaev.

Netchaev, a center, only played in 3 NHL games during his career, so it is easy to see how he is barely a footnote in history. These three games went to the history books though, because Victor was the first Soviet trained player to appear in the NHL, as well as the first to score a goal.

European hockey history expert Patrick Houda tells us more.

"Victor made his North American debut as a 27-year old in 1982 for New Haven in the AHL. He was off to a fast start in New Haven and scored 1 goal and 5 points in his first 4 games there. It was his 1 goal and 2 assist performance in a game vs. Adirondack that gave him the call up to Los Angeles Kings.

The historic date for his NHL debut was October 16, 1982 when he appeared in a Los Angeles Kings uniform. The game was vs. the New York Islanders at Nassau Coliseum.

"Netchaev was put on a line together with Darryl Evans and Steve Bozek. Kings lost the game 1-4 and Victor was held pointless in the game, but his performance was solid."

"The next night at Madison Square Garden, Victor beat Rangers goalie Steve Weeks 17:15 into the 1st period to make it 3-0 Los Angeles. His goal came on an assist by Darryl Evans and was the first ever goal in the NHL by a Russian trained player. Los Angeles went on to win 4-2 and Victor was one of the best players on the ice, having 5 shots on goal and being +1," says Houda.

"He only played sparingly in his third and last NHL game and was then sent down back to New Haven for conditioning purposes, as GM George Maguire put it."

Victor's son Greg offers more input on his father's career:

"My father was actually offered a contract by the Kings for 2 years plus one option. But he did not want to stay with the Kings for 2 years for fear of being moved down to the minor league. He actually just wanted a shorter term of time which would eliminate the probability of going down to the minor because of age (27). The third "game" at Forum, in Los Angeles against the New Jersey Devils, was the beginning of "North American" negotiations for a contract. During these negotiations he was stripped of his gear, forbidden to see, play, or practice with his team, and was almost metaphorically "jailed" for almost a month. "

"Being from the USSR, he was totally shocked by the lack of care or respect or even understanding of the needs of the player himself in the pro sports here. It seemed to him that money was first and this whole dilemma had nothing to do with the sport anymore. He also said that "It was very hard to work with the manager (George Maguire) who had busy hands, one hand with whiskey and one with a cigarette."

Although Netchaev had NHL offers from other teams (New York Rangers, Hartford Whalers), he opted to briefly play in West Germany with Dusseldorf.

But how did Netchaev escape the Soviet Union and come to play in the NHL? Houda gives us a look into Netchaev's background.

"He was born in Kuibyshevka-Vostochnaya in Siberia, Russia on January 28, 1955. He made his debut in the Russian elite league as a 17-year old for Spartak and had 16 pts (8 goals + 8 assists) in 20 games.

"The next season (1974-75) he played in the 2nd division for his home team Siberia where he had a fine season with 20 goals (32 pts) in 56 games. After that he got picked by SKA Leningrad in the Russian elite league where he played between 1975-80. During the 1980-81 season he split his time in two 2nd division clubs, Binokor and Izhstal where he scored 40 points (26 goals and 14 assists) in 40 games.

"That was Victor's last season in Russia. He met an American woman who he married and moved to USA, which made him miss the entire 1981-82 season."

The American woman with whom he fell in love with was Cheryl Haigler, a Yale graduate student studying abroad in Leningrad. They actually met in Switzerland in 1977, when Netchaev was playing in the Spengler Cup. They married in 1980 but she was forced to return to the United States because her visa expired shortly after the wedding. She took a job in Boston with an accounting firm, and began the two year legal process of freeing Netchaev to come to America.

The Kings got word of his arrival in America, and even though he was far from a top Soviet player they were immediately interested. He got drafted in 1982 by Los Angeles in the 7th round, 132nd overall.

What has Netchaev been up to since hanging up the blades. Son Greg fills us in on that:

" Since he left the ice, he was doing numerous things involving entertainment, managing, local television programs (russian), radioing (russian). Then, starting from 1991, he began working as a manager and director of development of players with his partner Serge Levin in ARTV Sports Management. From '92-94 he was also the assistant coach and international scout of the Milwaukee Admirals. He still works in ARTV Sports Management as his main business."

Victor scored 137 goals 234 points in 328 Russian league games and 4 goals and 11 points in 28 AHL games.

His NHL stats were nothing too impressive with 1 goal in 3 games, with a +1 rating and 7 shots on goal. But it was that first game and first goal that today is the trivia question. Who was the first Soviet trained player to score a goal in the NHL ? Not Fetisov, not Makarov, not Mogilny, not Bure, but a guy from Siberia named Victor Netchaev.

Brian Smith

The hockey world was shocked by the violent death of former Kings and North Stars left wing Brian Smith on August 2, 1996.

A popular television sportscaster for CJOH-TV in Ottawa, Smith was shot in the head in the parking lot outside his station following his sportscast July 31st, 1996. Police said that a 38-year old man was responsible for the shooting and that apparently the suspect was angry at members of the media and wished to cause harm to a media personality.

After 90 minute surgery Smith died on August 2 at Ottawa Civic Hospital. Brian was just 54 years old.

Brian's NHL career began with the Kings during the club's inaugural season, 1967-68. During the 67-68 campaign he played 58 games for the Kings recording 10 goals and 9 assists for 19 points. The following year he was dealt to Montreal and then Minnesota, where he played 9 more NHL games. He played a total of 10 years as a pro with nine teams, mostly in the minor leagues.

Brian had been employed at CJOH since 1973, the year after he retired from hockey. He was highly respected for his straight-talking, low-key style.

Brian came from a prominent local hockey family. His father, Des, was a member of the 1940-41 Stanley Cup champion Boston Bruins and his brother, Gary, was an NHL goaltender for 14 seasons with eight different teams earning him the nickname, "Suitcase Smith."

A popular television sportscaster for CJOH-TV in Ottawa, Smith was shot in the head in the parking lot outside his station following his sportscast July 31st, 1996. Police said that a 38-year old man was responsible for the shooting and that apparently the suspect was angry at members of the media and wished to cause harm to a media personality.

After 90 minute surgery Smith died on August 2 at Ottawa Civic Hospital. Brian was just 54 years old.

Brian's NHL career began with the Kings during the club's inaugural season, 1967-68. During the 67-68 campaign he played 58 games for the Kings recording 10 goals and 9 assists for 19 points. The following year he was dealt to Montreal and then Minnesota, where he played 9 more NHL games. He played a total of 10 years as a pro with nine teams, mostly in the minor leagues.

Brian had been employed at CJOH since 1973, the year after he retired from hockey. He was highly respected for his straight-talking, low-key style.

Brian came from a prominent local hockey family. His father, Des, was a member of the 1940-41 Stanley Cup champion Boston Bruins and his brother, Gary, was an NHL goaltender for 14 seasons with eight different teams earning him the nickname, "Suitcase Smith."

Brandy Semchuk

Brandy Semchuk enjoyed a lengthy career in the minor leagues because he could skate effortlessly. Too bad that's about all he could do. Semchuk never showed much offensive promise until he reached the lowly WPHL and WCHL some seven years after turning professional. Semchuk was a blazing skater used primarily in defensive and penalty killing situations through out most of his career.

Semchuk was drafted high, 28th overall by Los Angeles in 1990. This was due largely to his breakaway speed and the fact that he trained for two seasons with the Canadian National team as opposed to junior hockey. With the Nats he trained under Dave King, one of the top defensive teachers in all of hockey. However he left the program with lower back and groin injuries that nagged him for years.

The Kings gambled on him by taking him so early. He was an interesting prospect at the time - a young player who was very solid defensively and with great speed are two things often lacking in players that age. But Semchuk lacked an offensive element. As a result, he only played in 1 NHL game, against the Calgary Flames. While he scored no points, he did get on the stats sheet by taking a minor penalty.

After his minor league season was over in 1993, he was one of the Kings' minor league players asked to skate and practice with the Kings during their magical run to the 1993 Stanley Cup finals. Semchuk recalls having dinner with Wayne Gretzky as amongst his career highlights.

Semchuk opted to play out the final year of his contract in 1993-94, and that proved to be a mistake. Back in the minor leagues, Semchuk suffered a serious eye injury that ended his season. No team, not even the Kings, were interested in Semchuk after the scary injury. He continued on, catching on with minor league contracts in a variety of minor league cities until he finally hung up the blades in 1999. His eye never fully recovered full vision.

Last I heard Semchuk was living in Fresno, California, coaching hockey a youth hockey team named the Jr. Falcons. His daughter Emma was a promising player on the Jr. Falcons. He also was helping to coach a new junior hockey team, the Fresno Monsters.

Semchuk was drafted high, 28th overall by Los Angeles in 1990. This was due largely to his breakaway speed and the fact that he trained for two seasons with the Canadian National team as opposed to junior hockey. With the Nats he trained under Dave King, one of the top defensive teachers in all of hockey. However he left the program with lower back and groin injuries that nagged him for years.

The Kings gambled on him by taking him so early. He was an interesting prospect at the time - a young player who was very solid defensively and with great speed are two things often lacking in players that age. But Semchuk lacked an offensive element. As a result, he only played in 1 NHL game, against the Calgary Flames. While he scored no points, he did get on the stats sheet by taking a minor penalty.